Mapping The History of Mary Prince

Working with The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Related by Herself (1831), I am continuously struck by the extent Prince travels in the narrative, even before she arrives in London. Beginning in Bermuda, moving to the Turks and Caricos Island, back to Bermuda, then Antigua, and finally England, the text covers a wide swath of the Atlantic World. This a distance of approximately 11,035 kilometers (6,856.83 miles). To give some perspective, traveling due East from New York City, United States across the Atlantic Ocean and Europe to Tokyo, Japan is 10,849 kilometers (6,741 miles). Her ability to maintain and create new social networks covering such a large geographic space fascinates me, leading to the question of how best to represent this feature in my writing.

Historical maps (though the one above is a century too early). This, too, holds its challenges, since Bermuda is latitudinally closer to the Carolinas than to the Caribbean. As a result, I come across several maps where Bermuda is included through an aside, erasing a sense of the actual distance. I haven't really found the right historical map yet (although at a recent conference, someone had a wonderful Atlantic map, that I think will work including Britain without making the scale to large.) Another option is to use the line drawing option on maps through Neatline in Omeka, but I'm wary of how well this will work in a large scale map.

Google was useful for figuring out distances, and as I am working out locations within islands, planting markers as estimates of locations is useful. I also worked on trying to estimate where she traveled in Bermuda. I am also experimenting with warping historical maps onto Google. Here's an screenshot from Google Earth.

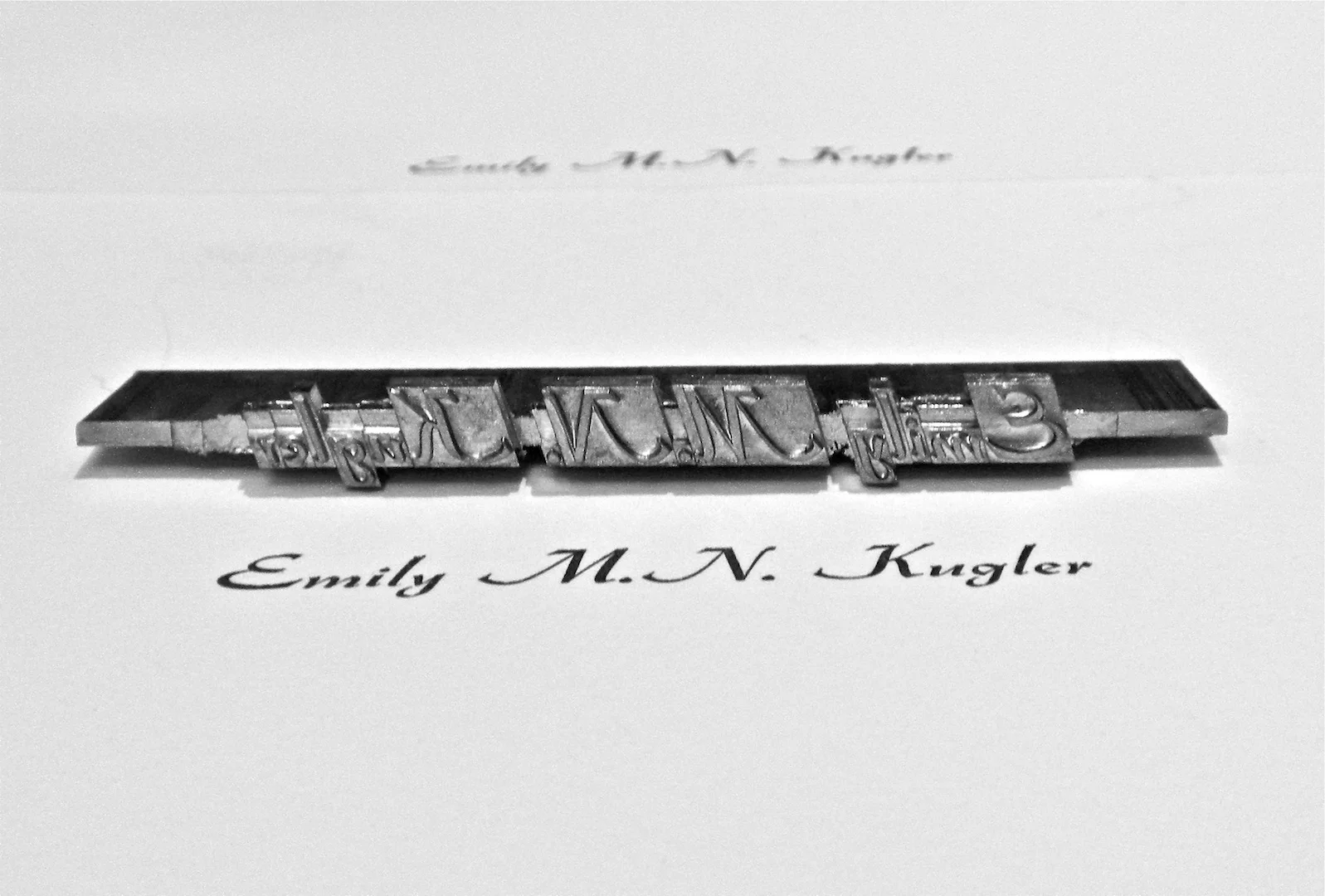

But what I also wanted to map was her relationships between spaces of family, owner households, and other social connections. In other parts of this project, I am working on tracing the network of The History as a non-human object, as well as visualizing the print history of its first three editions. But I am also fascinating with how Prince, like Olaudah Equiano [link], possesses a history very unlike the experience of most Atlantic World slaves, whom she is meant to represent to her abolitionist readers. Ironically, while she is presented as a model of a universal experience, the biographical details reveals in The History are singular and align with why she is one of the few enslaved women from her era—-and arguably any other—-to have her individual history published. As Moira Ferguson points out in her edition of The History, “most slaves had only one or two owners in a lifetime, whereas Mary Prince had five before she freed herself” (7). More extraordinarily, she frequently negotiated her own sale to new owners, pointing to the value of her labor, both in terms of the multiple jobs she could perform for an owner, as well as their ability to rent out her labor to others for a profit. In each new household she enters, she consistently forms new networks that often extend beyond her position as a chattel slave. She is born into a familial group that transcend owner households. Her mother is owned by a Mr. Charles Myners in Brackish-Pond Bermuda and her father by a shipbuilder, Mr. Trimmingham, for whom he works as a sawyer. That Mary Prince carries her father’s name, not her owners’ is significant, as is the relationship she maintains with her father throughout her time on Bermuda. When Myners dies, she, her mother, and sisters are sold to Captian Darrel Williams who gifts Prince to his granddaughter Betsey. Although Prince bonds with her young owner as a child, the experience illustrates how an enslaved woman cannot rely on her owners household for protection and support, even when there are affective bonds between owner and slave. When Betsey’s father sells her, he usurps the “rights” of his daughter from his first familial network to pay for the wedding to create a new one, disregarding old familial connections in order to forge new ones. As difficult as I find it to sympathize with The History’s portrayal of Betsy’s “rights” over another person, this scene emphasizes the multiple disruptions her father’s marriage creates. Mary’s family is split up and sold. Her sisters are not heard of again in the narrative, though she is able to stay in contact with her parents.

The slave market scene, with the tragic separation of mothers from young children, the editor Pringle points out, echoes similar stories from other sales around the Atlantic. Certainly British abolitionist readers would have recognized this scene from those they read and collected in their albums. But what happens after her sale to Captain I. differs from those narratives filled with images of passive victims looking to heavens for help to arrive, perhaps from a good middle-class woman from a Birmingham anti-slavery society. Her future is certainly shaped by the particular social relationships she formed with the Williams. She bonded with her biological family, as well as the women of the Williams family, but more importantly, she had experience using her labor to create relationships outside of the household. Rented out to work for a Mrs. Pruden, Prince must have learned to work with those outside of her immediate circles, by moving five miles away (think of how far this is to walk) in the next parish. When she is sold to the Ingrahms at Spanish Point, she understands her new owners’ cruelty through their treatment of the old French slave Hetty and two young boys. When Hetty’s death leads to Prince taking up the abused woman’s work, she describes less the physical violence she experiences, but her expectation of it through her knowledge of Hetty’s experiences. To escape this, she fleas back to her parents, where her mother hides her in a cavern until her father returns her to her owners. Note here that Prince’s familial network is still accessible to her, but ultimately provides no permanent protection.

When we look at Bermuda human actors by status, there are clear separations (Network 1).

The next network looks a kinship networks, which again is disconnected.

But when we look at household (owners, children, enslaved), the network becomes more centered on Mary Prince, with her father disconnected from her network nodes.

Her next sale breaks the limited effectiveness of those familial connections when she is sold to Mr. D who takes her to Turks Island (approximately 1371.85kilometers, 852.43 miles away, roughly the distance from New York to Birmingham; to give a bit of perspective, later in the century Harriet Tubman would bring people from slavery in her home state of Maryland roughly only 500 miles north to her head quarters in St. Catherine’s Canada as a means of feeling safe from the Fugitive slaves act).

Even when she does see her mother on the island (76), her mother with a new daughter in hand, temporally “lost her senses” as she “had never been on the sea before.” On Turk’s Island, Prince lacks a network, in part it seems to the hard labor she is put through, as well as to the lack of a population there with which to create a network. In these scenes she turns to the English reader as a new network for these spaces (74). (This will be expanded upon in another post).

Within the narrative this foreshadows how her religious networks will allow her to leave the Woods when they travel to London, and reflects back onto the network that produced the pamphlet. To their surprise, despite severing her from a community she knows through personal interactions, she is still able to access her Antigua networks through the Moravian church. This allows her to leave their service, with The History acting as both the first abolitionist slave narrative in English dictated by an Black colonial woman as well as a sign of her voice in a new network: the Anti-Slavery Society.

What I am playing with now is a spatial and human network. I'm including places such as Turk's Island, but also the cavern on Bermuda where Mary Prince meets with her parents after running away. In this rough draft, countries are not their own nodes, and are listed more often than needed. I'm also including organizations, such as abolitionist and religious organizations. In csv for UCInet, I'm working on how to mark the different actor categories.

Prince’s ability to create new networks is a unique skill that sets her apart, even from her family members. Pringle points out in a footnote that unlike Prince’s ability to keep in contact with her father when with the Ingrahms, her father “had been long dead and buried before any of his children in Bermuda knew of it.” Her mother died shortly after her last sale to the Woods in Antigua, and of her “seven brothers and three sisters, she knows nothing further than this - that the eldest sister, who had several children to her master, was taken to him to Trinidad; and that the youngest, Rebecca [whom she met when her mother went to Turk’s Island], is still alive [as of 1831], and still in slavery in Bermuda” (76). Yet, some contact was still kept.

When we think of her past with networks, her ability to move into new communities and find allies, and her record of turning her enslaved labor into a tradable skill, is it so hard to imagine that she also used this in London. Her authorial authority may not fit the conventional models, relying instead on a transcriber and editor to find a public voice in print. Yet, this ability to negotiate a network here ensures her independence from the Woods, her ability to stay in London (albeit away from her husband), and though the reports of her physical deterioration in the second and third editions are presented as pitiable, they are also serving a means to raise funds to support her (an option not available to her in the West Indies). As with her laundry, her agency with The History is not one of the free liberal subject found in Enlightenment philosophies of individual sovereignty. This model, though, was able to sustain the systems of power that continued slave systems and other forms of institutional oppression. The model of subaltern agency offered by Sharp better fits the history of Mary Prince and The History bearing her name.

Although she was meant to represent all slaves, and indeed frequently points to her observations on many islands of many slaves in her appeal to English audiences to end slavery in the colonies, her ability to navigate multiple networks leading to her self-manumission makes her singular. Yet, in other ways, The History illuminates a colonial archive that goes beyond the stories of West Indian slavery or English abolitionist groups. It demonstrates the global networks of an abolitionist movement that went beyond a binary of enslave black colonial and white English abolitionist. For Strickland and Pringle are better described as British than English, representing the complicated way that the rest of the British Isles and wider empire worked to agitate for political change in the governmental center, came into conflict in their shared endeavors, and also fit a wider sense of empire. This is not one empire, with a clear hierarchy offering clear roles and ranks to its subjects. Instead, as The History and its history shows, it is a set of interlocking international networks, in which actors play many—-sometimes contradictory— roles, and where empire could at times unite people in a central cause or set different networks of the ruling class in opposition to one another.

NB: Notes to be posted later